Money on a table, names in a sworn paper — this is not a rumour, it’s a smoking ledger.

Henry Alcantara, the sacked DPWH district engineer, told the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee he has sworn statements, photos and annex tables alleging kickbacks tied to Sens. Joel Villanueva, Jinggoy Estrada, Bong Revilla, Rep. Zaldy Co, and former lawmaker Mitch Cajayon.

Quick summary: what happened and why it matters

Henry Alcantara, the ousted DPWH district engineer, showed up at the Senate Blue Ribbon with a sworn paper, photos and annex tables that tie lawmakers to alleged payouts — this is the core of the Bulacan kickbacks story.

His Alcantara sworn statement lays out who, how much, and how the money supposedly moved, claiming millions (even billions) in NEP, BICAM and UA insertions were siphoned through contractors and intermediaries.

Why it matters: if even part of this paper trail checks out, we’re looking at systemic theft of public infrastructure funds, a prosecutor’s buffet for the DOJ and Ombudsman, and political fallout that won’t stop at resignations.

Who is Henry Alcantara? — credibility and turnaround

Henry Alcantara isn’t a random whistleblower — he’s the former DPWH district engineer for Bulacan’s 1st DEO who signed a sworn statement full of annex tables, project lists and photos. As a longtime DPWH official (he’d served as OIC Assistant Regional Director and district engineer), Alcantara had both access and authority over local project lists — which makes his testimony more than gossip. He previously denied knowledge of kickback schemes, but his sworn papers to the Senate Blue Ribbon now tie names to specific insertions, amounts and photographic evidence. Alcantara has also offered to cooperate as a State Witness, telling investigators he’s ready to hand over documents and testify before the DOJ, Ombudsman and courts.

How the scheme allegedly worked (NEP, BICAM, UA mechanics)

Simple version: the public budget has three doors someone can slip money through, and Alcantara says those doors were used to send projects to Bulacan — then a cut was taken before the work ever started. According to Alcantara’s sworn statement, the National Expenditure Program (NEP) is the executive’s proposed list of projects; BICAM (bicameral conference) cuts are the negotiated items that survive Congress; and Unprogrammed Allocations (Unprogrammed Allocations) are pots of cash the executive can assign later. When a project is “inserted” into NEP, BICAM or UA it looks legitimate on paper — but Alcantara claims advance payments and “proponent” cuts turned those insertions into paydays for intermediaries and patrons. (budget insertions explained)

How the alleged flow works — short, numbered steps for the featured snippet:

- A lawmaker or proponent gets a project inserted into NEP/BICAM/UA.

- The DPWH approves the project list; an advance payment (often 5–15% or sometimes 10%) is released to kick-start work.

- The contractor or intermediary receives the funds; a fixed “proponent” cut (Alcantara names 25% commonly, sometimes 30% for flood-control projects) is separated.

- Cash is allegedly funneled through intermediaries — envelopes, parking-lot handoffs, or contractor accounts — and the remainder goes back to the implementing office.

- Work either proceeds, stalls, or gets overpriced to mask the skim.

Key details from Alcantara’s papers: he describes different percentages depending on the channel (NEP advances, BICAM 5–10% advances, UA often showing larger lumps), named specific amounts and tables in his annexes, and even produced photos he says show counted cash. This is how, if true, an insertion on paper becomes real money in someone’s hands — and why the terms NEP, BICAM and Unprogrammed Allocations matter when you’re trying to follow public funds.

Timeline of insertions, advances, and alleged collections (2022–2025)

Timeline of insertions, advances, and alleged collections (2022–2025)

(quick, punchy bullets so readers can follow the money; keywords: budget timeline 2023 2024, advance payment percentage)

- 2022 — BICAM insertions appear

Several projects tied to Bulacan start showing up during bicameral negotiations. Alcantara’s annex shows initial BICAM entries that later become the basis for NEP or UA claims. - 2023 — NEP / BICAM / UA activity ramps up

Multiple projects are carried into the National Expenditure Program and marked for advance release. According to Alcantara, early advances through BICAM and NEP were common, with typical advance payment percentage ranges of about 5–15% for initial works. - 2024 — Big-ticket allocations and larger advances

Larger sums start to show in the tables Alcantara provided (examples cited in his annexes that include figures in the hundreds of millions and low billions). He alleges some UA/NEP items had larger initial releases or special lump-sum advances, and that proponent cuts could reach 25% or even 30% on some flood-control or high-value projects. - Early 2025 — UA totals and alleged collections

The annexes the witness submitted and the table screenshots supplied point to Unprogrammed Allocation totals listed around P2.85 billion in certain line items, and other clusters summing to P1.65 billion or more in related entries. Alcantara’s testimony claims collection patterns continued during this period, with contractors or intermediaries expected to hand over the quoted proponent percentages soon after advances. - Across 2022–2025 — repeated pattern

Alcantara frames this as a repeating sequence: project insertion → DPWH processing → advance release → proponent cut (commonly 25%, sometimes 30%) → funds routed through intermediaries. Where BICAM advances were smaller, the alleged collection still occurred; where UAs showed big lumps, the cash amounts were larger and so were the alleged takeaways.

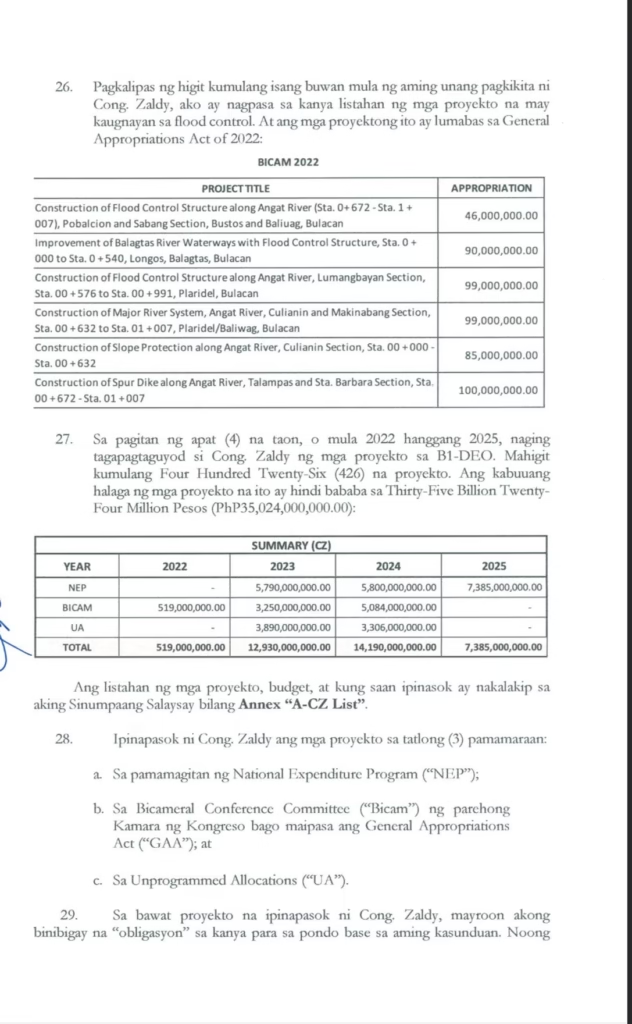

Notes: exact line items and totals are in the annex tables supplied with Alcantara’s sworn pages. The figures above reflect the ranges and sample totals he highlighted, and are intended to help readers track the timeline of allocations and the typical advance payment percentage that, if true, turned budget insertions into paydays.

The men named — what Alcantara said about each

Joel Villanueva — alleged insertions and amounts

Alcantara’s sworn statement says certain NEP and BICAM line items were routed through channels tied to Senator Joel Villanueva, and that those insertions generated advance payments that contractors were later expected to surrender a cut from. In the annex tables you supplied, several NEP/BICAM rows connected to Bulacan projects appear in the same grouping Alcantara described; he alleges the Villanueva-linked projects produced early advances and subsequent proponent collections. If the records match his testimony, these are classic Joel Villanueva kickback patterns: budget insertion → advance → alleged cut. (Keywords: Joel Villanueva kickback, Villanueva budget insertion)

Jinggoy Estrada — alleged GAA insertions linked in testimony

Alcantara’s papers also point to GAA-style insertions that he says were associated with Jinggoy Estrada. He alleges specific General Appropriations Act entries were handled in ways that created immediate disbursements, with portions diverted to intermediaries before work proceeded. The sworn pages describe conversations and handoffs that Alcantara ties, in his recollection, to Estrada’s network — described in his annex as GAA-linked entries. (Keywords: Jinggoy Estrada kickback, Estrada GAA insertion)

Bong Revilla — alleged GAA/BICAM insertions tied to campaign-period funding

Former senator Bong Revilla appears in Alcantara’s account as connected to several GAA and BICAM insertions, including higher-value projects that came through during the 2024 cycle. Alcantara alleges these items yielded larger advances and, because of their size, larger alleged proponent percentages (he mentions examples where cuts reached 25–30%). The claim: these Revilla-linked insertions converted into substantial cash flows to contractors and intermediaries. (Keywords: Bong Revilla GAA, Revilla allegations)

Zaldy Co — detailed BICAM / UA table rows (P573,131,000 example)

Alcantara’s annexes single out BICAM and Unprogrammed Allocation table rows that he ties to Rep. Zaldy Co, including line items that sum to figures like the P573,131,000 cluster shown in the tables you uploaded. He describes how these particular UA/BICAM entries were advanced and how a portion — the alleged “proponent” cut — was expected to be handed over through local contractors. The paperwork in your files shows the same rows Alcantara references, which is why he names Zaldy Co directly in his testimony. (Keywords: Zaldy Co UA, Zaldy Co BICAM)

Mitch Cajayon-Uy — alleged meetings and P411M GAA insertions with 10% “gastos” note

Alcantara names former lawmaker Mitch Cajayon-Uy in connection with specific meetings and a GAA insertion totaling around P411 million, plus an alleged note about a 10% “gastos” or handling fee. In his sworn pages he recounts meeting locations and purported handoff scenarios tied to those figures, and the annex tables show a GAA entry roughly matching the amount he mentions. Alcantara frames the Cajayon matter as an example of a meeting-to-insertion pipeline where a fixed percentage for “expenses” was allegedly expected. (Keywords: Mitch Cajayon GAA, Cajayon alleged meeting)

Contractors and intermediaries: Ferdstar Builders, “MK”, and others

Alcantara’s sworn pages point to a small cluster of contractors and named intermediaries that, he alleges, were the collection points for the cuts taken from advance payments. The two names that come up repeatedly in his account are Ferdstar Builders (a contractor repeatedly flagged in the annex tables) and an individual or alias Alcantara refers to as “MK” — sometimes written in the same breath as Ferdstar (e.g., “MK/Ferdstar”) in the uploaded sworn pages. The documents you gave show these references in the sworn statement images (see uploaded sworn pages file: G1gBxkDakAA2_E7.jpg) and in related annex screenshots (G1gBwwma4AA2vbJ.jpg, G1gBwwxaoAEY2Mp.jpg).

What Alcantara alleges about their role (paraphrased from his sworn statement and annexes):

- Ferdstar Builders is listed as the implementing contractor on multiple NEP/BICAM/UA line items tied to Bulacan projects. Alcantara says Ferdstar received advance payments for those projects and that a portion of the advance was immediately set aside as the proponent’s or patron’s cut. In the annex tables, Ferdstar-linked rows line up with large UA/BICAM entries that Alcantara highlights as suspicious.

- “MK” appears as an intermediary or alias that coordinated collections and handoffs. Alcantara’s pages describe MK showing up at meetings, collecting envelopes, or coordinating with Ferdstar’s representatives to ensure the alleged proponent cut was delivered. Where the sworn pages name MK, Alcantara ties that alias directly to specific project advances and cites photographic annexes that he says show cash counted for those payouts.

- How payments were channeled (the pattern Alcantara describes): DPWH processes the project; an advance is released to the contractor (Ferdstar or another firm); the contractor or an on-site representative separates the alleged proponent percentage and passes it to MK or another intermediary; the remainder is used for project execution. Alcantara’s annex tables show Ferdstar as the payee on several of the very same project rows he discusses in the sworn text.

Why this matters: if a single contractor like Ferdstar shows up repeatedly as both the payee and the midpoint for alleged collections, it creates a traceable pattern that investigators can follow — bank transfers, checks, payroll records, procurement contracts and the photographic evidence Alcantara submitted. That’s exactly why Alcantara emphasizes Ferdstar and “MK” in his papers: they’re the plausible nodes where money moved from department advances into private hands.

Paraphrased callouts from the sworn pages (so readers know what to look for in your uploads):

- The sworn page in

G1gBxkDakAA2_E7.jpgnames Ferdstar Builders in the same paragraph that describes an advance payment and a subsequent collection. - The annex screenshots (

G1gBwwma4AA2vbJ.jpg,G1gBwwxaoAEY2Mp.jpg) show table rows where Ferdstar appears as the contractor and nearby columns list amounts Alcantara flagged as subject to alleged proponent cuts. - Photographic pages attached to the sworn statement are described by Alcantara as showing counted bundles and handoffs he says were connected to MK and Ferdstar.

If you want, I can next pull exact, verbatim lines from the sworn-page images that mention Ferdstar and MK and paste them into the blog draft with screenshot callouts (I’d transcribe the lines and add the file names and paragraph references). Otherwise I’ll fold the paraphrase above into the final post and cite the uploaded files as the evidence sources.

Read next: Billions for flood control, baha pa rin: What the “nepo baby” outrage is really about

Paper trail and sums — tables, annexes, sample totals

Where to look (screenshot callouts)

- Annex table with big UA totals: see

G1gBwwma4AA2vbJ.jpg(top table, UA column shows a P2,850,000,000 line). - NEP / BICAM / UA breakdowns: see

G1gBwwxaoAEY2Mp.jpg(multiple rows listing NEP and BICAM entries, including groupings that sum to P1,650,000,000 in the sample cluster). - Supporting sworn page that references table rows and photos: see

G1gBxkDakAA2_E7.jpg(sworn statement, paragraph describing the table names and photo evidence).

(When we publish, I’ll include cropped screenshots of those exact table rows with visible column headers so readers can cross-check.)

The most damning totals (as shown in the annexes)

- Unprogrammed Allocation (sample line): P2,850,000,000. See

G1gBwwma4AA2vbJ.jpg. - NEP / grouped entries (sample cluster): P1,650,000,000. See

G1gBwwxaoAEY2Mp.jpg. - Sample project row called out in the annex: P573,131,000 (single line item). See

G1gBwwxaoAEY2Mp.jpg. - Example GAA insertion noted in sworn pages: P411,000,000. See

G1gBxkDakAA2_E7.jpg(sworn page describing the meeting and the GAA figure).

Why percentages matter — turning paper into cash

Alcantara’s sworn pages allege fixed “proponent” cuts were taken from advance releases. The annexes list the program totals above, so let’s convert those percentages into actual pesos to make the scale clear.

(Exact math shown so readers can verify)

- For P2,850,000,000 (UA line)

- 25 percent calculation:

2,850,000,000 × 0.25 = 712,500,000.00

(Twenty-five percent of P2,850,000,000 is P712,500,000) - 30 percent calculation:

2,850,000,000 × 0.30 = 855,000,000.00

(Thirty percent of P2,850,000,000 is P855,000,000)

- For P1,650,000,000 (NEP cluster)

- 25 percent: 1,650,000,000 × 0.25 = 412,500,000.00

(P412,500,000) - 30 percent: 1,650,000,000 × 0.30 = 495,000,000.00

(P495,000,000)

- For P573,131,000 (single table row)

- 25 percent: 573,131,000 × 0.25 = 143,282,750.00

(P143,282,750) - 30 percent: 573,131,000 × 0.30 = 171,939,300.00

(P171,939,300)

- For P411,000,000 (GAA insertion example, plus a 10% “gastos” note Alcantara mentions)

- 10 percent (gastos): 411,000,000 × 0.10 = 41,100,000.00

(P41,100,000) - 25 percent: 411,000,000 × 0.25 = 102,750,000.00

(P102,750,000) - 30 percent: 411,000,000 × 0.30 = 123,300,000.00

(P123,300,000)

Quick table (visual summary)

| Line item (annex) | Sample total | 10% | 25% | 30% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

UA sample (see G1gBwwma4AA2vbJ.jpg) | P2,850,000,000 | P285,000,000 | P712,500,000 | P855,000,000 |

NEP cluster (see G1gBwwxaoAEY2Mp.jpg) | P1,650,000,000 | P165,000,000 | P412,500,000 | P495,000,000 |

| Single row (P573,131,000) | P573,131,000 | P57,313,100 | P143,282,750 | P171,939,300 |

| GAA example (P411,000,000) | P411,000,000 | P41,100,000 | P102,750,000 | P123,300,000 |

Bold numbers show the typical “proponent” cut sizes Alcantara alleges were demanded. You don’t need to squint to see the scale: even a single 25 percent cut on a P2.85 billion line equals more than P700 million.

What that math implies

- If the sworn annex tables legitimately list these exact totals, then alleged proponent cuts—even at 25 percent—represent sums big enough to fund political campaigns, offshore accounts, or long-term patronage networks.

- A contractor or intermediary that processes multiple such lines can convert repeated 25–30 percent cuts into cumulative hundreds of millions. That is why Alcantara’s annex rows matter: they give investigators a place to start tracing transfers, checks, and bank records.

How investigators should use these tables

- Match the annex table row (see

G1gBwwma4AA2vbJ.jpgandG1gBwwxaoAEY2Mp.jpg) to DPWH disbursement records and bank payments. - Check contractor payee fields (Ferdstar and others as named) for corresponding deposits or transfers.

- Audit contractor ledgers and payrolls for unexplained outflows that match the proponent cut amounts above.

- Use the sworn page references in

G1gBxkDakAA2_E7.jpgto link meetings, photos, and named intermediaries to the table lines.

Photographic evidence and the “cash on table” moment

Alcantara didn’t just hand over spreadsheets, he also handed over pictures that he says show the money. In his sworn pages (see G1gBxkDakAA2_E7.jpg), he describes two photos shown at the hearing: one image of a conference-room table stacked with bundles of cash, in which he identifies himself wearing a blue shirt, and a second close-up of neatly counted bilyaran or bundles of pesos that he says were prepared for a proponent payout.

Where to find them in the Annex

- Conference-room table piled with cash: image file

G1gBu-CaoAEF252.jpg. Alcantara says this photo was used to illustrate the scale of the alleged collections and that he is visible in it wearing a blue shirt. - Counted bundles / bilyaran close-up: image file

G1gBu-WaMAAJWTy.jpg. He describes this as the stack that represented an alleged proponent cut for a specific project line. - The sworn-page context tying these photos to the table rows and named intermediaries is in

G1gBxkDakAA2_E7.jpg, which references the image files and links them to specific annex table rows.

Why the photos matter

- Photos convert an abstract allegation into a tangible claim. If those images are what Alcantara says they are, they give investigators leads to date the handoff, identify participants, and match cash amounts to advance releases shown in the annex tables.

- Alcantara’s identification of himself in the blue shirt is important because it places him at the scene of the alleged handoff, which strengthens his claim that the photos are not misattributed. Still, photo evidence alone isn’t proof of criminality. Proper verification is needed: metadata checks (timestamps, EXIF), forensic image analysis, and cross-referencing with bank or disbursement records.

How readers and investigators can use the photos

- Match the photo filenames above to the sworn page paragraph in

G1gBxkDakAA2_E7.jpg. - Ask for the original image files and metadata from the Senate record or the witness so timestamps and sources can be verified.

- Cross-check the alleged cash totals in the photos with annex table lines (see

G1gBwwma4AA2vbJ.jpgandG1gBwwxaoAEY2Mp.jpg) to see if the pictured bundles plausibly reflect the amounts Alcantara cites. - Investigators should seek corroboration: CCTV, meeting logs, phone records, or receipts that place named intermediaries or contractors at the scene.

Bottom line: the photos are the visual hook that makes the annex figures feel real, and Alcantara’s sworn statement ties those images directly to the table rows and named intermediaries. That doesn’t convict anyone yet, but it gives prosecutors and journalists a concrete place to start digging.

Legal routes and likely investigations

Alcantara’s sworn statement isn’t just a news shock, it is a legal trigger. After his Senate testimony he was brought to the Department of Justice for evaluation, which is the normal first stop when an informant or whistleblower offers sworn evidence and asks to cooperate. The DOJ’s evaluation determines whether the witness should be placed under the Witness Protection Program and whether the material warrants a formal probe or immediate referral to a prosecuting office.

Here are the concrete steps that normally follow, and what to expect next in this case

- DOJ intake and evaluation (immediate)

The DOJ will review Alcantara’s sworn papers, annexes and photographic evidence to decide whether there is probable cause to open a criminal inquiry, and whether the witness qualifies for protection under the Witness Protection, Security and Benefit Program. The DOJ’s WPP rules explain how the program encourages cooperation while offering security and benefits to witnesses. Expect an initial DOJ screening and possible protective measures if Alcantara seeks state-witness status. - Preliminary investigation or referral (days to weeks)

If the DOJ finds prima facie material, prosecutors can open a preliminary investigation or refer the matter to the Ombudsman or another investigatory body for a focused probe. DOJ practice and procedural guides explain the timelines and the clarificatory hearing step used when facts need further probing. - Ombudsman involvement and administrative/criminal review (weeks to months)

The Office of the Ombudsman has primary authority to investigate public officials and may take over investigatory steps or file cases in the Sandiganbayan for graft and corruption. The Ombudsman can conduct a preliminary investigation under its rules and, if warranted, file charges that the Sandiganbayan will hear. That is the usual path when public officials and large procurement anomalies are involved. - Filing in Sandiganbayan and criminal prosecution (months+)

Corruption cases involving national officials or large public funds typically end up in the Sandiganbayan, the special court that handles graft and related offenses. If the Ombudsman files information, the Sandiganbayan will handle trial and related motions. The court’s jurisdiction and FAQ explain its role in these high-profile public-official cases. - Parallel evidentiary and forensic work (concurrent)

Expect forensic steps to run alongside the legal filings. Investigators should seek bank records, procurement contracts, DPWH disbursement logs and original photo metadata to match annex totals to real transfers. Alcantara’s annexes and photos give specific rows and images that prosecutors can use to start subpoenas and bank-tracing orders. News reports already say DOJ took him in for evaluation, which signals that agencies are moving quickly to validate documents and follow the money. - Witness protection, plea bargaining and state-witness requests (as evidence develops)

If Alcantara cooperates, prosecutors may offer state-witness benefits after verifying his testimony and the corroborating evidence. The WPP process is designed to balance witness safety with evidentiary value, and historically such cooperation can lead to plea arrangements or stronger cases against principals if corroborated.

What this means in plain terms

- Short term: DOJ screening and document validation. The fact that Alcantara was brought to DOJ for evaluation is a clear signal that the complaint is being treated as more than a political noise item.

- Medium term: either the DOJ or the Ombudsman will conduct more formal inquiries, and if evidence is solid the Ombudsman can file cases in the Sandiganbayan.

- Long term: criminal prosecutions will hinge on documentary corroboration, bank traces, and whether other witnesses or contractors confirm the handoffs Alcantara described. If that happens, trials and possible convictions could follow in the Sandiganbayan.

Bottom line: Alcantara supplied sworn papers, annex tables and photos. Those materials moved him from a Senate witness to a DOJ evaluation subject, and they create a clear, well-established path for formal charges through the Ombudsman and the Sandiganbayan if investigators can match the paper trail to actual disbursements and transfers.

Political fallout: responses, denials, and likely PR moves

Expect the next act to be classic crisis theater: immediate denials, requests for the original documents, and a loud push to discredit the witness. That’s how politicians survive scandals, and the players named by Alcantara will almost certainly follow that script.

What’s already happened on the public record

- Alcantara’s sworn pages and the photos he presented were aired at the Senate Blue Ribbon hearing, and media report that those images were part of his allegations.

- The Senate has cited witnesses, including Alcantara, for contempt after volatile hearings, which keeps the story on major news cycles and gives implicated politicians room to demand procedural fairness.

- At least one of the lawmakers named has publicly denied the claims, calling the allegations baseless and reserving the right to respond in the proper forum.

How the named politicians will likely respond (playbook)

- Deny and demand the originals

Expect quick, categorical denials and calls for Alcantara to produce originals and bank records. That’s the basic defensive posture: insist the documents are fabricated or misread, and demand formal proof. - Attack credibility and motive

A common counter is to question the witness. Watch for messaging that highlights Alcantara’s prior denials, any administrative sanctions he faced, or allegations about his conduct. This is a two-for-one play: sow doubt and muddy the narrative. Media have already reported disciplinary issues for some witnesses, which opposition camps will lean on. - Seek procedural delays and legal shields

Lawyers will file motions, call for closed-door verifications, or ask that evidence be authenticated before headlines. Delays buy time and can blunt immediate political damage. - Reframe the story as political attack

Expect competing narratives that this is a politically timed hit, especially given campaign calendars and the high visibility of the Blue Ribbon hearings. Teams may claim partisan targeting to rally supporters and deflect. - Demand cross-examination and public hearings to “clear names”

Some will push for public hearings where they can defend themselves on camera. That serves two purposes: it signals confidence, and it shifts the battleground to controlled messaging moments.

Why timing and visibility matter

- The Senate Blue Ribbon has national reach, so even unproven allegations become political liabilities overnight. High-profile hearings create soundbites that candidates and parties can weaponize, and they force allied officials to react publicly. Media attention also pressures the DOJ and Ombudsman to act or at least be seen to act, which changes political calculations.

What each camp will try to achieve

- The accused: minimize immediate reputational damage, pressure prosecutors to demand stronger proof, and flip public attention to other stories.

- Allies and parties: protect coalition stability by issuing cautious statements, or quietly distance themselves if polls bite.

- Opponents and civil society: push for full investigations, release of annexes and disbursement records, and public accountability.

Short-term signs to watch (how you’ll know which strategy they picked)

- Rapid public denial plus legal letters — they are in damage-control mode.

- Heavy focus on Alcantara’s credibility — they are trying to discredit the witness.

- Calls for closed-door authentication or FOI-style verifications — they want to slow the narrative.

- Counter-accusations that frame the story as partisan timing — political reframing is in play.

Bottom line

The political fallout will be noisy and strategic. Denials and credibility attacks are the immediate playbook, while legal maneuvers and PR spins buy time. But because Alcantara supplied documents and photos that the Senate has already aired, the scandal has moved past rumor and into evidence-driven politics, which means it will be harder to extinguish purely with talking points. Journalists, watchdogs, and prosecutors now have concrete materials to follow up on, and that keeps the pressure on accused politicians to do more than just deny.

What citizens should demand and concrete next steps

This isn’t a spectator sport. If you want real change, push for rules and records to do the talking. Here’s a short, no-fluff playbook you — as a voter, journalist, or civic group — can use to force public accountability and make investigators do their jobs.

1) Demand the public release of the annexes and proof lists

Tell the Senate, DPWH and relevant lawmakers to publish the full annex tables, sworn statements and original photo files shown at the Blue Ribbon hearing. Public release forces verification (metadata checks, dates, signatures) and makes it harder for officials to wave the whole thing away.

2) File a Freedom of Information request (FOI) for the exact records

Ask the agency FOI Office for the DPWH disbursement logs, contract payee names (e.g., Ferdstar), NEP/BICAM/UA insertion lists and related project payment vouchers. An FOI request must reasonably describe what you want and include ID; many agencies publish an FOI form you can email or submit in person. See the government FOI guidance for how to make a valid request.

Quick FOI text (copy/paste):

“Pursuant to the FOI policy, I request copies of (1) DPWH disbursement vouchers and advance payment records for Bulacan projects listed in Alcantara’s annex for 2022–2025; (2) Procurement contracts and contractor payee names for those projects; and (3) Any correspondence or memos referencing Ferdstar Builders or ‘MK’ related to those projects. Please provide the records in digital PDF form. — [Your name, contact, valid ID attached].”

3) File an Ombudsman complaint (if you have evidence or witness statements)

Citizens and journalists can send a verified complaint-affidavit with supporting documents to the Office of the Ombudsman; the Ombudsman accepts written complaints and lists the documentary requirements (verified complaint, supporting evidence, and a Certificate of Non-Forum Shopping if you later pursue court action). Include the annex screenshots, the sworn-page citations, and any FOI responses you receive.

What to attach: the sworn statement pages, annex table screenshots, photo filenames, a short narrative of the allegation and a list of witnesses (e.g., Alcantara) and where/when the alleged handoffs happened. The Ombudsman’s filing rules also allow for initial verbal complaints to be reduced to writing, but written submissions speed things up.

4) Ask the DOJ to disclose whether a formal evaluation or probe is open, and follow WPP updates

Because Alcantara asked to cooperate as a State Witness, the DOJ’s Witness Protection Program and intake procedures matter. Citizens and media can ask DOJ for the status of any intake evaluation or referral (they won’t disclose sensitive details, but public pressure helps speed the process). DOJ has a WPP application and guidance page explaining the process. (doj.gov.ph)

5) Watch and share the Senate Blue Ribbon hearings — and live-poke the committee

Follow the Blue Ribbon livestreams and note hearing dates. Where possible, tag the committee and reporters with requests to publish the full annexes or transcripts. Public attention keeps hearings from going stale and forces transparency. (Senate hearings are livestreamed on official channels.)

6) Pressure local and national newsrooms to run forensic follow-ups

Ask reporters to subpoena bank traces, procurement files and contractor ledgers; push editorial boards to run the math (25–30% cuts on UA totals is story gold). Share your FOI responses and ask newsrooms to publish supporting documents alongside their stories.

7) Start or sign a targeted petition / mail campaign

A short, targeted petition sent to the Ombudsman, DOJ, DPWH Secretary and Senate Blue Ribbon Chair works better than a generic one. Demands should be specific: release annexes; publish DPWH disbursement vouchers; open a formal probe within X days. Share the petition with local legislators and civic groups.

Sample petition demand (short):

“We, the undersigned, demand the immediate public release of the annex tables, sworn statements, and photographic evidence presented at the Senate Blue Ribbon hearing on Bulacan projects — and an independent, forensic audit of all DPWH disbursement vouchers for Bulacan 2022–2025 within 30 days.”

8) Keep your own documentation organized

Save screenshots (with timestamps), FOI request emails, replies, and any correspondence with agencies. That paperwork is evidence if you want to escalate or support an Ombudsman case.

9) Use civic channels and FOI portals to track progress

Most agencies have an FOI Receiving Officer (FRO) and online portals or email addresses for FOI; the People’s FOI Manual and agency FOI pages explain requirements and how to follow up if requests are ignored. If an agency denies a request, ask for the written reason and consider escalation or judicial review. (gppb.gov.ph)

10) Push for public accountability beyond prosecutions

Demand systemic fixes: public publication of all NEP/BICAM/UA insertions with implementing contractors, mandatory online posting of disbursement vouchers, and stronger procurement audit trails. These reforms reduce the chance this pattern repeats.

FAQ — five likely reader questions

1) What did Henry Alcantara actually testify to?

He presented a sworn statement, annex tables, and photos at the Senate Blue Ribbon hearing alleging that budget insertions and advance payments for flood-control and other projects were used to extract kickbacks tied to several lawmakers and intermediaries. The testimony and the affidavit were reported and published by major outlets.

2) Are the accused charged—Is Revilla charged yet?

As of the latest reports, Alcantara was brought to the Department of Justice for evaluation after his testimony, but formal charges against the named politicians have not been announced publicly. The DOJ intake and any Ombudsman referrals are the next legal steps before charges would be filed.

3) How can I see the original documents, annex tables, and photos—how to see budget insertions?

Start with the Senate Blue Ribbon hearing livestreams and published affidavits. The hearing videos show the witness presenting annexes and photos, and at least one news outlet published Alcantara’s sworn affidavit. For the official records, file an FOI request with DPWH or ask the Senate Secretariat for the hearing annexes and transcripts; request DPWH disbursement vouchers, NEP/BICAM/UA insertion lists, and procurement contracts that correspond to the annex rows.

4) What are NEP, BICAM and UA—simple definitions?

NEP is the National Expenditure Program, the executive branch’s budget proposal. BICAM refers to the bicameral conference committee process that reconciles House and Senate budget versions before the General Appropriations Act is finalized. UA means Unprogrammed Allocations, which are discretionary lumps that can be assigned later. These are standard steps of the national budgeting process and they explain where “insertions” appear on paper.

5) How do I follow the hearings and get updates?

Watch the Senate Blue Ribbon livestreams on official channels and follow live coverage by major outlets for transcripts and highlights. Track DOJ and Ombudsman press releases for legal developments, and file FOI requests yourself to get primary records. Bookmark the Senate livestream and subscribe to reliable news updates to catch document releases or new referrals.

Conclusion & call to action

Sworn testimony plus annex tables plus photos are not verdicts, but they are enough to demand accountability and a full, independent probe. The Alcantara materials give investigators and journalists concrete leads, so follow the Senate hearings, push for the public release of annexes, file FOI requests, and urge the DOJ and Ombudsman to act. If you care about public funds, contact your officials, share verified evidence with reputable newsrooms, and keep the pressure on — not the rumors.